ABSTRACT For this third installment of The Philosophical Touch column, Rolfer® Andrew Rosenstock explores the philosophical origins and deeper meaning of the term ‘somatics’. It emphasizes that somatics, coined by Thomas Hanna in 1976, refers to the body as experienced from within, rather than as an external object. The modern usage of the word somatics can at times be reduced to a buzzword, referring to slow or gentle practices, which overlooks its philosophical depth. For Rolfers, reclaiming the somatic perspective shifts their work from technical interventions to relational and perceptual offerings centered around the client’s lived experiences.

“The soma is the body as experienced from within.”

Thomas Hanna (1988, 20-21)

The Philosophical Touch column is about the intersectionality of somatic bodywork and phenomenology, and is dedicated to the late Jeffrey Maitland, PhD (1943-2023), a treasured Advanced Rolfing® Instructor, philosophy professor, and author. My wish is to remind the structural integration community to challenge dualistic thinking when considering human structure and function. In the first column, I discussed language being like a mirror, the nature of meaning, prioritizing the client’s lived experience, and linking mind and body as intimately connected (Rosenstock 2024).

In the last column, I explored that the body is not merely a vessel passively experiencing life; it is an active participant in perception, movement, and making sense of the world (Rosenstock 2025). I discussed the works of Austrian-German philosopher Edmund Husserl (1859-1938), the principal founder of phenomenology, and Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1908-1961), a French phenomenological philosopher. Their work supports us as somatic practitioners; it’s through perception and responsiveness that our work truly comes alive. This article will continue to build on all these topics, bringing in the philosophical roots of embodiment, with a spirit of looking beneath the surface.

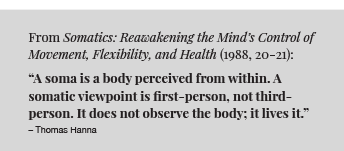

Let’s turn now to the word somatic, a term many of us use without always pausing to ask what it actually means. Not what it’s come to mean in popular culture and common usage, but what it meant originally when philosophy professor and movement theorist Thomas Hanna (1928-1990) coined it in 1976 to point toward lived, first-person experience (1988).

Today, somatic is used to describe everything from slow movement practices to trauma work, to anything that involves sensing the body from within. While those uses aren’t entirely wrong, they often miss the depth and precision the word once carried. In Hanna’s original framing, somatics wasn’t a technique or a trend. It was a philosophical stance – a way of recognizing the body not as an object to be acted upon, but as a living, perceiving subject.

That distinction changes everything.

And it didn’t come from nowhere. Hanna drew from a rich philosophical lineage that includes Edmund Husserl and Maurice Merleau-Ponty – thinkers who insisted that perception is not something added on to the world, but something through which the world arises. To be somatic, in this sense, is not simply to slow down or turn inward. It is to live from within the world as a sensing being.

For Rolfers, this orientation matters. It shifts how we understand change, how we attune to the client, and how we make contact – not just with the body, but with the lived experience that body holds.

The Coining of Somatics: Hanna’s Original Intent

In the 1970s, Thomas Hanna recognized a missing thread in the way we talked about the body. As a philosopher, educator, and practitioner, he saw how the dominant language of anatomy and medicine treated the body as an object – something observed from the outside, measured, diagnosed, and corrected.

But that wasn’t how people lived in their bodies.

What he proposed was simple yet radical: we need a term that speaks not to the body as thing, but to the body as self. The body as felt. The body as experienced from within.

And so, he coined the term somatics – from the Greek soma, meaning the living body in its wholeness – not separated into parts, not viewed from the outside, but encountered subjectively.

Hanna wasn’t just inventing a word. He was reclaiming a way of knowing.

To be somatic, in his usage, wasn’t about a particular method. It wasn’t about being gentle, or slow, or trauma-informed – though all these can be expressions of somatic awareness. What Hanna named was an epistemology: a mode of perception grounded in internal experience, as opposed to detached analysis.

In Hanna’s original framing, somatics wasn’t a technique or a trend. It was a philosophical stance – a way of recognizing the body not as an object to be acted upon, but as a living, perceiving subject.

This was not a retreat from science. It was a call to include the observer – the feeler, the mover, the one who lives in the body – as a valid and essential part of understanding what the body is.

Hanna’s ideas build on the work of Husserl and Merleau-Ponty. He didn’t invent somatics so much as he gave a name and a frame to something philosophers had long been circling. In that sense, he was less a revolutionary and more a restorer – someone who found a pair of scuffed shoes, overlooked and gathering dust, and shined them just enough for people to notice their beauty again. His real contribution was in bringing these embodied insights into a practical field where they could be felt, practiced, and taught.

Lived Experience: From Husserl to Merleau-Ponty

Before Hanna, the idea of the lived body had already been carefully articulated by phenomenologists – those thinkers who turned philosophy toward direct experience, away from abstraction and toward perception itself.

Edmund Husserl made a crucial distinction between two German words for “body”:

Körper – The body as object, visible, measurable, and external.

Leib – The body as lived, felt, and inhabited from the inside.

This distinction – between the anatomical body and the lived body – opened the door to a new way of thinking. Instead of studying the body from a clinical remove, phenomenologists asked: What is it like to be this body? What can be known only from the inside.

What Hanna named was an epistemology: a mode of perception grounded in internal experience, as opposed to detached analysis.

Merleau-Ponty, expanding on Husserl’s ideas, brought this inquiry into full articulation. In the Phenomenology of Perception (1945, 146), he writes:

“The body is our general medium for having a world.”

For Merleau-Ponty, perception is not something we do to the world – it’s how the world shows up to us at all. And it shows up through the body, not just to it.

This wasn’t a metaphor. It was ontology, the nature of being.

We do not stand outside our bodies, looking in. We live through them. We are them – not in a mechanical sense, but in a relational, perceptual one. The world and the body are not two separate domains. They co-arise.

Hanna absorbed these ideas and distilled them into language that could meet the felt sense of practitioners and clients alike. Where Merleau-Ponty spoke of reversibility, perception, and the flesh of the world, Hanna translated this into somatics: the study and practice of embodiment from the inside out.

To remember the lineage is to remember that somatics is not a trend or a technique. It is a philosophical reorientation toward lived experience – a turning inward that does not retreat from the world, but reveals how deeply intertwined we are with it.

To remember the lineage is to remember that somatics is not a trend or a technique. It is a philosophical reorientation toward lived experience – a turning inward that does not retreat from the world, but reveals how deeply intertwined we are with it.

When a Word Loses Its Depths

In recent years, somatics has become something of a buzzword. It shows up on websites, in yoga classes, movement workshops, and various therapeutic modalities. It’s often used to mean something like: slow, gentle, internal, or trauma-aware.

And while those qualities can indeed be somatic in nature, they aren’t what somatics actually means. Not originally.

When the word is reduced to a style of movement or a flavor of therapy, we lose the philosophical precision Hanna intended – and with it, the depth of orientation that gives our work meaning.

Hanna wasn’t naming a method. He was naming a way of knowing.

To be somatic is not to perform a technique. It’s to operate from a first-person perspective. It’s to recognize that the body is not just something to be observed, improved, or fixed, but a subject, a self, a living, experiencing, unfolding from within.

This confusion isn’t just linguistic – it has consequences for practice. When we mistake somatic for “soft,” “slow,” or “movement-based,” we risk flattening the range of what somatic awareness actually offers. We start thinking we need to change our technique to be more somatic, when in fact what needs to shift is our perception – how we listen, how we attend, how we meet the client’s world from within their lived body, not just their structure.

And this is especially important in Rolfing® Structural Integration. Because we already work with tissue, sensation, orientation, and perception. But if we forget the root of what somatics means, we risk working on bodies, rather than with somas.

When we forget the original meaning of somatics, we risk reducing our work to a set of interventions. We become technicians, aiming to fix structure or optimize function, rather than practitioners engaging with lived, dynamic beings.

Why This Matters for Rolfers®

At its core, Rolfing Structural Integration is not just a manual technique. It’s a perceptual practice – a relational art rooted in how we meet, sense, and respond to the living humans before us.

When we forget the original meaning of somatics, we risk reducing our work to a set of interventions. We become technicians, aiming to fix structure or optimize function, rather than practitioners engaging with lived, dynamic beings.

But when we reclaim the somatic perspective, something shifts. Our contact becomes less about correcting and more about listening. Our interventions become invitations. Our goals soften, not because we’re less effective, but because we recognize that true change doesn’t come from imposing – it comes from meeting.

Fascia doesn’t change because we pressed hard enough. It changes because the system sensed something – and chose to reorganize. That sensing happens from within. And to meet it, we too must work from within – within ourselves, within our clients’ perceptual field, within the relational flow that emerges in each session.

This is what it means to be a somatic practitioner – not because we do a certain thing, but because we attend in a certain way. So, when we say ‘somatic’, let’s remember what we’re pointing to. Not just the body. Not just movement. Not even just presence.

We’re pointing to a way of knowing. A way of being. A way of returning again and again to the place where life is lived – not from the outside looking in, but from the inside out.

In reclaiming the depth of the word somatic, we’re not just honoring a lineage – we’re restoring clarity to the lens through which we practice. As Rolfers, we work with bodies, yes, but more truly, we work with lived experience. With sensing, perceiving beings. And when we remember that, our work deepens, not because we do more, but because we meet what’s already there, more fully.

Andrew Rosenstock is a Certified Rolfer®, Registered Somatic Movement Therapist, Biodynamic Craniosacral Therapist, Board Certified Structural Integrator, Certified 1000 Hour Yoga Therapist (C-IAYT 1000), Certified Rolf Movement® Practitioner, meditation teacher, Esalen® Massage practitioner, and a whole bunch more. Outside of bodywork, Rosenstock enjoys travel, reading, and time with his wonderful wife, beautiful daughter, and adorable dog. Find out more at andrewrosenstock.com and rolfinginboston.com.

Fascia doesn’t change because we pressed hard enough. It changes because the system sensed something – and chose to reorganize.

References

Hanna, Thomas. 1988. Somatics: Reawakening the mind’s control of movement, flexibility, and health. New York, NY: Perseus Books.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. 1945. Phenomenology of perception. Translated by C. Smith in 1962. Publisher Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Rosenstock, Andrew. 2025. The philosophical touch: Embodied awareness. Structure, Function, Integration 53(1):16-20.

Rosenstock, Andrew. 2024. The philosophical touch: How Wittgenstein can enhance somatic therapies. Structure, Function, Integration 52(2):13-16.

Keywords

somatics; soma; Thomas Hanna; phenomenology; embodiment; lived experience; perception; Maurice Merleau-Ponty; Edmund Husserl; Rolfing Structural Integration; fascia; ontology; somatic awareness; internal experience; perceptual practice. ■

View all articles: Articles home