ABSTRACT By Dorothy Miller, Certified Advanced Rolfer™, and Mary Bond, Certified Advanced Rolfer, Rolf Movement® Instructor Emeritus

Editor’s note: The title of this piece is a quote from Ida P. Rolf, PhD (1896-1979), in the book Ida Rolf Talks about Rolfing® and Physical Reality (1978), page 181. The authors speak about this particular quote in the article.

Body Mandala and Beyond

Dorothy Miller: Thank you for joining me in this conversation. As a somatic educator, Rolf Movement® practitioner, and Certified Advanced Rolfer™, you are an expert in our June 2025 main theme – how human beings balance while moving. Thank you for taking the time to share your understanding.

In your books, Your Body Mandala: Posture as a Path to Presence (2018) and Body Mandala: Posture, Perception, and Presence (2023), you use the beautiful geometric pattern of the mandala to teach people how to find balance in their bodies. I have Your Body Mandala, 2018, on my bookshelf. Your movement ideas are a joy to read and practice. Personally, I find myself comfortably revisiting the practices in the book for myself and my clients. As my body, my Rolfing® practice, and the way in which I work with my clients continues to evolve, the exercises that you have in your book are so foundational and profound. I never fail to appreciate them.

In the years since your book came out, do you find yourself satisfied with the messages? It’s like you’ve made a gift to the world with these movement suggestions. Do you have more to say?

Mary Bond: Thank you Dorothy, first for appreciating it and also for making use of it. That’s really what I was after, that people would find a way to use it in their own self-care and to translate it for themselves into how they work with clients. And, yes, I have more to say. I am forever interested in the body. I don’t know whether another book is the way to do it. People seem to put books on shelves.

When offered to do a second edition by the publisher, there was an opportunity to make improvements in it. But it was a busy time for me, so I didn’t. Later I thought that I would have liked to address what I call the interoceptive midline differently because I don’t teach it the way it’s presented in the book anymore. But because midline is referenced fifty times in the book, the changes would have had to be pretty extensive, and by that time it was past the deadline. And I realized it didn’t really matter to my overall message, so I had to let that go.

There was also more to be said about Dr. Neil Theise’s work with the interstitium [see page 6 for an interview with Dr. Theise]. It’s a different point of view about the importance of fascia. I wrote that I thought interstitium was a better name than fascia. Interstitium means in-between things, and fascia just means bandage. But that didn’t make the second edition either, and continues to draw my attention.

Preparing for this interview, I was looking back through the book and was reminded of all the scientific information I researched to support my own themes. But I haven’t retained all that information, so I was learning things just like a reader would.

DM: That must have been fun. Readers of the book will discover that it takes more than just doing exercises to inhabit our bodies differently. It takes curiosity about dynamic balance. Not only are we feeling what’s within our body and how it’s connected, but we also understand our relationship with the space around us, our relationship to gravity, and the concept of biotensegrity – an organizing principle for human structure.

Just out of curiosity, what is your elevator speech when you tell someone about Body Mandala? What is a mandala in this context?

MB: A mandala is a visual representation of universal harmony that is used in Buddhist meditations and other religions (see Figure 1). It symbolizes the search for enlightenment. In the book, your body is the focus of the meditation through which you’re cultivating a relaxed, open, and responsive way of being present in your life – an enlightened body. And, as a side effect, you also become more physically balanced and upright. Is that short enough for an elevator ride?

DM: Yes, and beautifully said.

MB: I was surprised when the book first came out, it seemed like most people didn’t know what a mandala is.

In the second edition (2023), they changed the title, removed ‘Your’ and the subtitle became Posture, Perception, and Presence. ‘Posture’ is the hook for the general public because people don’t think much about perception. But for me, perception is the real message. Most people are only aware of sensations of pain and extreme pleasure. But our everyday sensations are rich in wisdom. By learning to listen to our body wisdom, we can save ourselves a lot of trouble.

that is used in Buddhist meditations and other religions. It symbolizes the search for enlightenment.

DM: Definitely. When I talk to clients about my work, I emphasize preventative care. When people are able to have a more embodied experience, they can adapt to situations more quickly and often avoid injury, especially overuse injuries. It’s very empowering for people to realize they can achieve a perceptual shift through these meditations, which can result in more efficient movement and less discomfort.

MB: And really, you can’t maintain a shift if you don’t feel it. It’s really important that we help our clients to value their sensations.

MB: And really, you can’t maintain a shift if you don’t feel it. It’s really important that we help our clients

to value their sensations.

Movement Explorations

DM: You have a movement exercise called “curling into hammock,” which is one of my favorites. You describe reflexive coordination and activation of core stabilization muscles, and that’s just not something that you hear about often in traditional strength training. Could you tell us a little more about that?

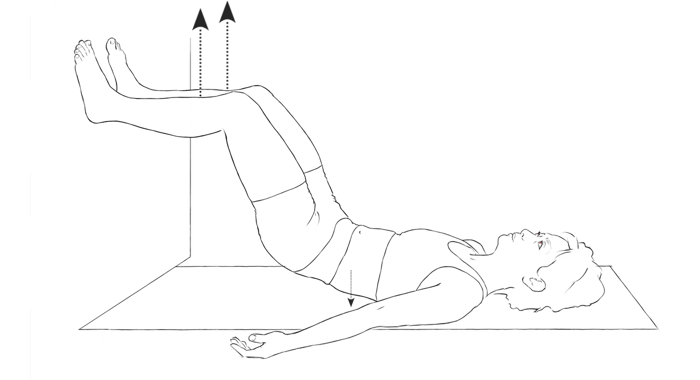

MB: Sure. First of all, curling into hammock is a variation of what Dr. Rolf called the pelvic lift. For years I was playing around with the pelvic lift, which I think is poorly named. Nevertheless, that’s what we call it and it has to do with integrating the spine with the pelvis and the sacrum.

I found that by putting the feet on the wall, people could get a better sense of that relationship than if the feet are on the floor or on the table. That is what the hammock exercise essentially is (see Figure 2).

To give readers a little context, in 1999 an Australian group headed by Carolyn Richardson came out with a book entitled, Therapeutic Exercise for Spinal Segmental Stabilization in Low Back Pain. It was about activating core muscles, and the fitness community got on the bandwagon. Fitness coaches started teaching pain management through strengthening the deep abdominal muscles. But the research was actually indicating that managing low back pain depended on the precise timing of muscle activation. So, it’s not about strength per se. It’s not about having rock-hard abs.

The hammock exercise makes use of your perception of the space outside of your body by using imaginary vectors into space through specific locations on your body: the feet, the tibial and ischial tuberosities, and the lumbar segments. It’s a kind of spatial fantasy that sets you up for what I think of as tensegrity-informed movement.

When your focus is on your perception of space (through those imagined vectors), sensing your body’s weight expands your awareness of space inside your body. So, when your body moves through that expanded volume, it changes your timing and your muscles come online as required without your having to think about it. They just do it.

The hammock movement is an invitation to this kind of orchestration rather than a series of solo muscle control coming from your cortical brain. When we invite movement that feels fluid and powerful but not so effortful, it can diminish back pain. But how does it work?

I think that being big, having volume, is a normal state of our bodies that begins to diminish when we go to school and we’re made to sit still and to more or less leave our bodies in order to develop our minds. I think it’s normal for human movement to be expansive. And when it is, you get that timing phenomenon, which is absent when the body is more compressed. When your body is compressed, you begin to use your thinking brain to manage movement.

DM: That compression seems like it might come from the bracing that people do to avoid pain, or for whatever reason, they’ve adopted this habit. It can really impact expansive movement because they tend to use their larger locomotor muscles for postural stability.

Following your movement cues for the hammock meditation, it’s not like I’ve told some of my muscles to turn off, they just do. Your instructions lead a person only as far as they can support in that moment. It feels like a safe way to allow the smaller postural muscles to participate.

For me, one of the hardest things to access is that reflexive coordination piece, those little postural muscles that haven’t been working for so long because they haven’t had a chance. I have personal experience with low back pain and the hammock exercise was particularly meaningful.

MB: There’s another piece to that, Dorothy. By moving very slowly through the unfolding of the spine, or through the lifting up, curling upwards of the pelvis in the other direction, all of that feeds our capacity to fully sense what we’re doing. It’s only by sensing deeply that you can integrate it so that it becomes useful.

So, what you’re doing by practicing that slow, careful, sometimes tedious movement is teaching your body to be bigger and to be able to really operate the way it’s meant to operate, in contrast to training at a gym, where we may be getting more compressed by repeating things over and over.

Complementing Content with Video

DM: I appreciate that your books include access to videos for the meditations. It is so helpful to see the demonstration. Having a guide makes a huge difference.

MB: Right, thank you. Both Body Mandala books (2018, 2023) incorporated video into the book because many people wrote to me after The New Rules of Posture (2006), saying they wanted to see what I was talking about. So, that’s what I did. I made a DVD called Heal Your Posture: A 7-Week Workshop (2016). It can be purchased and streamed on vimeo.com. It's storyline is different from The New Rules (2006), but it teaches the same exercises.

In both books the video links are right in the text. Many people are getting the audiobook as well. They read the book, view the movement videos, and can listen to it while doing the explorations. So they are getting more of their senses experiencing the content of the book.

DM: That’s an enriched experience. What a good idea to lie down and listen to the book while exploring the movements.

MB: Exactly. Without the audio, you have to stop, pick up the book and read the instructions. That doesn’t work as well.

DM: The meditations in your book are super effective, but they do take time, and it takes a commitment to them to create lasting change.

Offering Movement Suggestions for Clients to Take Home

DM: Manual therapists have limited time with clients; we have to keep an eye on the clock. Do you have any thoughts about ways that manual therapists can efficiently integrate this work into their sessions?

MB: Yes, staying on time can be a big problem. We have so much to offer our clients and change takes time, like

you said.

My aim in writing Body Mandala (2018, 2023) was to share what I had learned from working with French Rolfer Hubert Godard in the 1990s. His work made me aware of my orienting perceptions. That is, the perception of my relationship to the ground and my perception of the objects, the people, and the events in my environment – basically, my spatial awareness.

Orienting is about finding your sense of being safe in the present moment. Unconsciously you ask yourself, “Where am I? What’s going on here?” By valuing my perceptions and by gradually expanding my own orienting repertoire, I found more physical ease and confidence, more freedom to express myself. Those seemed like gifts to be shared, hence the book. And this is where the “presence” in the subtitle comes in.

I would suggest that for manual therapists to integrate the movement suggestions into their sessions, a necessary step would be to embrace them in their own bodies first. I haven’t found any shortcuts. It takes time. It just does. It can take a long time. But as you’re working on it for yourself, you begin to notice other people’s orienting tendencies. Or at least the tendencies they bring into the therapy session with them.

Then you can begin to tailor your sessions and the things you say to your clients about movement according to the perception that tends to be underactive in them. For example, if a client is more reliant on the ground to feel safe, you might help them expand their perceptual repertoire by introducing awareness of the space around their bodies.

There’s an exercise in chapter three called “moving from the back of your head” (see Figure 3). I actually learned it from Jane Harrington [Rolf Movement Instructor - Emeritus] decades ago, but there it is in the book. Evoking spatial awareness that way could become a recurring theme for that client throughout your work with them.

DM: I use that one a ton, especially when I’m trying to help people with either rotation or general movement at the atlas-occipital joint. I’ve never had a client who didn’t understand it when I explained that most of our life is in front of us. So we all have a really good connection to the space in front of us. The space behind us is often ignored and underused. Guiding people into sensing their occiput and the space behind them can make a big difference, especially for those who have neck and shoulder pain from sitting at a desk all day.

Somatic Education

DM: I want to take a moment to share with our readers how powerful your courses are as well, your way of teaching micromovements is so effective. I know for me, as I embody the work, your instruction made the process much easier for me to teach it to my clients and help them shift into new patterns. I’d love to know if you’re planning any classes for practitioners in the future.

MB: It’s great to know that it helps you and thanks for the endorsement. Since the COVID-19 quarantine, I’ve mostly been teaching online workshops, and most of the participants are somatic educators of some stripe or another. They do Tai Chi, Pilates, yoga, or Hanna somatics. There are also people who Google posture and discover me and they show up in my classes too. So, I’m teaching a whole range of people, and maybe a third of them are structural integrators. As a result, I keep my topics fairly broad, but I’m always sticking Dr. Rolf’s messages about gravity and fascia in there. Also Godard’s sensory approach to teaching movement. That’s my real agenda – our work inspired by these two great teachers. I share what seems appropriate for my wide variety of participants. These people are all interested in the body and it’s a great opportunity to help everyone understand the importance of gravity. People take from the training what they need. Recordings of all those classes are available on Vimeo. It’s easy to get access to watch them (see vimeo.com/marybond/videos). And, lately, I’ve been repurposing some of those videos for deeper study with small groups.

DM: Yes, I did the pelvis course you offered like that, it was wonderful.

MB: I also do some one-on-one coaching and mentoring online. I love when I get to work with students in real time. It’s a challenge for me to organize classes for myself. If someone else does it, I’m happy to teach in person. Last year, there were some classes in Europe and one in Hawaii.

DM: The SFI Journal editor, Lina Amy Hack, showed me the very first issue of this journal, called The Bulletin of Structural Integration (Bond 1969). It has an article written by you, “Implications of the Theory of Structural Integration for Movement Therapy.” We were wondering what it was like working with Dr. Rolf to publish a movement article in the first issue of this journal.

MB: That paper was an assignment for a course in “Dance Rehabilitation” at UCLA. I must have written it while I was receiving my first Ten Series in 1968. It reminds me of the way I crafted writing assignments back then, piecing together the viewpoints of various authorities but without a central premise of my own. I doubt Dr. Rolf read it beyond the first few paragraphs that introduce her belief that structural integration aimed at ‘evolution leading to a greater mankind’. To be honest, it’s a bit cringeworthy now, but it does make me appreciate how far I’ve come as a writer.

2025 Movement Explorations

DM: What kind of movement topics are you exploring these days?

MB: I am playing around with the concept of tensegrity in movement. It’s what has emerged from combining tensegrity’s relationship between tension and compression and Godard’s integrated relationship of spatial and ground orientations.

I’ve been curious about how biotensegrity as an organizing structural principle influences movement (Martin 2022). Tensegrity incorporates the element of space into structural balance. This is so different from the ‘stack of blocks’ lining up with gravity that Rolf focused on, even though with her concept of span (renamed palintonicity) she certainly understood that space was involved in integrating structure. And this leads me to Godard’s work about the integrative function of balanced space and ground orientations. There are some fruitful correlations to be made in all that, I think.

We orient ourselves before we begin to move, so we can feel stable and safe. A person usually prefers to orient to the ground or to the spatial environment. As a part of movement education, we invite clients to cultivate their underused perception.

That was what I was suggesting earlier. When a ground-oriented person begins to open their perception to their surroundings, that creates a more spacious body. It’s more upright, more balanced, and guess what? Better posture and more orchestrated movement.

For more space-oriented people, some tissue may be held upward, so their bodies also become less spacious. For them, learning to embrace the weight of the body as they sense the ground helps promote expansion..

I was musing on all of this as I was developing the book. It led to the thought that balancing one’s perceptual orientation was a tensegral activity, like the balancing of tension and compression. In the book I called this perceptual tensegrity, and the hammock exercise is an example of that.

When the book was finally done, I forgot all about perceptual tensegrity until a couple of years ago. It’s led me to begin a new quest, and this time I really want to understand it and not just journalistically. There is a growing worldwide community of somatic educators and movement teachers also who have become fascinated with fascia and biotensegrity.

Keeping Up with Fascia

DM: Where do you go to get current information about fascia and movement research?

MB: Lately I’ve been delving into the archive of written and recorded materials on a website you may have heard of – the Fascia Hub – it’s an organization out of the UK (see https://thefasciahub.com/who-we-are/about-us for more information). They have a collection of key academics like Dr. Jean Claude Guimberteau, John Sharkey (MSc, clinical anatomist), Joanne Avison (international anatomy instructor), Jaap Van der Wal (PhD, MD), and Stephen Levin (MD).

DM: They are great, I’m also a member. I would recommend their Fascial Heart webinar from a couple of years ago, it was phenomenal.

MB: They’re so great, I’m glad you know about it. I’m not very science-minded, so when I’m looking at those research papers, I read them more than once, but it’s starting to sink in.

I like starting out with the Fascia Hub website when I want the new information that is becoming available. I also like understanding what impact all this research could have on how we are teaching movement. So, now, I’ve read a lot of papers and watched some webinars, which leads me to playing around with my own movement. I stick with my explorations enough to see that a real understanding of these subjects pokes holes in much of what we think we know about the body.

For example, that structure is integrated by aligning its weight units, or that movement is achieved by hinges, levers, and pulleys. And the words ‘tensegrity’ and ‘fascia’ get tossed around to attract clicks from the search engines. In the marketplace, you see ads for ‘tensegrity yoga’ and ‘fascialites’. I’m not kidding, they are out there.

DM: Wow, okay.

MB: Yup, these are some of the fancy new buzzwords for wholism and body connectivity. I’m a wordsmith, and this bothers me when language is used superficially.

Typically, movement teachers use a tensegrity model to convey the idea of ubiquitous connectivity in the body. But that’s a superficial understanding of those models, like my own a couple of years ago. I used to see a one-to-one correspondence between the wooden struts and the bones, and the rubber bands and the soft tissues, fascia. One little tensegrity toy and you’ve got fascia and tensegrity all summed up.

A tensegrity model is a metaphor for the functional principle of the relationship between compression and tension; between compression elements that push outward and tension elements that pull inwards. So, structural organization is a result of this relationship between in-pulling and out-pushing forces. A structure like that doesn’t require gravity to maintain its shape. This was interesting to me. It made me think, “Uh-oh, gravity isn’t everything.”

DM: It isn’t everything, and yet it exists.

MB: Yes, right! When I chew on these topics, my mind goes way back to sixty years ago when anatomists thought of fascia as laboratory waste. Back then, Dr. Rolf understood it as the organ of structure, which is certainly one of its roles.

I think Dr. Rolf must have had her own perceptual experience of fascial continuity because she practiced yoga, and she had experience with osteopathic practitioners in getting help for her own body. I think she felt this. She didn’t have access to the present-day research that tells us that it is actually through the fascia that she was feeling what she was feeling. Right?

DM: Absolutely.

MB: Fascia is a bona fide sensory organ. This is very good for us to think about, that the proprioceptive feedback we get from fascia when we have a Rolfing session or a movement session is what makes it sustainable after we’ve left the office or studio. It’s what makes the work, work.

I think it was [Certified Advanced Rolfer] Rosemary Feitis (1937-2018) who said, something to the effect of, what you feel is what you keep. From my time taking classes with Dr. Rolf, I think that what she was trying to convey with that visual template of vertical and horizontal lines was that regarding the body as a whole is essential. She was trying to help us to see with that grid, to look beyond the muscles, to see the whole picture. Then, [one of Rolf’s students, founder of Aston Kinetics™] Judith Aston observed that the underlying reality of those perpendiculars resulted in spiral motion. For Dr. Rolf, that observation was a little step too far. She liked her verticals and perpendiculars.

I remember in one of my classes with Dr. Rolf, she asked a student named Kalen Hammond to write about tensegrity and Buckminster Fuller. I remember because he had an interesting name, and the paper was so good that it was printed up as a leaflet. I’ve looked and looked for it, but it’s gone. If anybody reading this interview remembers this, please contact me (see https://healyourposture.com/). I would love to see that essay again.

Support Is Relationship

MB: Dr. Rolf also spoke about spatial organization and appropriate tension in the tissues. I have a quote from Ida Rolf Talks (1978), may I read it to you?

DM: Oh, please do.

MB: This is from page 181:

“In a human body, support is not something solid. Support is relationship. Support is a balance of elements that aren’t solid at all, elements that are incapable of withstanding the weight that presses down on them, except as they are balanced. Could you translate this balance as tone? I don’t know. I don’t know what tone is in words, only in experience. I once equated it with span, but I don’t know how to define span. When you get span in a body, you get tone; When you get tone, you get span. Span is a spatial thing; tone is physiological. Both words refer to balanced structure in a living body. Both tone and span indicate a readiness to act and respond. And that is the touchstone of a healthy body.”

That sounds like a description of tensegrity to me.

DM: It really seems like she’s also speaking of that reflexive coordination that you talked about. That healthy tone is not overprotective, hypertonic. It is the tone that results from the movement, the bare necessities, the amount of tone required to maintain balance and support. As opposed to the typical high tonality of some places in people’s bodies and low tonality in other places of the same person.

MB: Yes, exactly. Also, I’ve learned that fascia is pre-stressed. This state is a characteristic of living tissues, a base level of tone associated with being alive. You don’t just have flabby old fascia doing nothing. It’s the fabric that’s pulling in on the bones while they are pushing out. In structural integration we think so much about releasing fascia. The fitness world talks about releasing fascia in some pretty aggressive ways. There can be places where dehydrated fascia needs to be rehydrated somehow or another. But the end result is not the absence of any tension whatsoever.

DM: This makes me wonder what happens to our tissue during a surgical procedure because that space would lose its pressure balance.

MB: That surgical aspect is how Stephen Levin got into this whole concept of biotensegrity, the tensegrity of living organisms. That is different from tensegrity.

DM: Thinking about all these musings together makes me wonder what is alive for you in your current movement practice? Do these ideas have you moving differently?

MB: Yes. And in exactly what we are talking about, experiencing the body as a tensegrity system. The idea that the structure is maintained by this balance of tension and compression. And that tension is not a bad thing. Stress is not necessarily a bad thing. There’s an appropriate degree of stress. And achieving that expansive balance in our bodies gives us support and strength through sharing the load throughout the whole body. Rather than being strong by contracting certain muscles, strength and balance can be found through spaciousness. That really intrigues me.

A favorite book on this whole topic is Living Biotensegrity: The Interplay of Tension and Compression in the Body (2022) by Danièle-Claude Martin. She’s a mathematician and a teacher of Tai Chi. She describes how tensegral movement has dynamic spaciousness, resistance, strength, internal support, omnidirectionality, spirality, efficiency, dynamic equilibrium, opposition, optimal recruitment, and what she calls, comfortable self-stress. I love this list. When I watch a dancer’s or an athlete’s performance that takes my breath away, I think this is what I’m seeing - tensegral motion.

How do we teach that? Not just teach, but release the imbalances that prevent us from finding it? Martin describes her teaching approach in her book, and it seems pretty derivative of Tai Chi. She’s very much in favor of very slow movement and a feeling of resistance in the body. As if you’re moving through thick air or Jello. It gives you this tension-compression feeling as you move. When I tried out this kind of movement after reading her book, I did feel bigger, more spacious, and fluid. So, that’s the kind of thing that I find inspiring these days.

I already mentioned the UK Fascia Hub, another one of their experts is author and yoga instructor Karen Kirkness (2021). Her work is looking at the embryological influences on the shapes of joints and how that dictates spiral motion. Also, she looks at how to teach yoga in a way that honors and respects those characteristics.

As I’m developing my movement practice, part of it is derived from things Ida Rolf taught me. I’m looking to help myself and others restore the expansiveness that we’ve all lost along the way. Perhaps I’ll discover a set of spatial cues that can be applied to any movement practice, and to anything a person does in daily life. Movement as commonplace as rolling over in bed.

I hope that gives you an idea about my tinkering with movement.

DM: Oh, yes. And thank you so much for your time today, for speaking with me and the readers in the printed article. We honor your career as a Rolfer and movement expert.

MB: It has been a pleasure to have this conversation with you, Dorothy.

Mary Bond has a master’s degree in dance from University of California, Los Angeles, and trained with Dr. Ida Rolf as a structural integration practitioner. Formerly chair of the movement faculty of the Dr. Ida Rolf Institute® (formerly the Rolf Institute® of Structural Integration), Bond teaches workshops tailored to the needs and interests of various groups such as dancers, Pilates, yoga and fitness instructors, massage therapists and people who sit for a living. Her articles have appeared in numerous health and fitness magazines and she hosts a popular blog at www.healyourposture.com.

Dorothy Miller is a Certified Advanced Rolfer™ living in Bend, Oregon. She is a lifelong learner and is passionate about furthering her understanding of the human body. She loves languages, traveling, hiking, skiing, swimming, and biking. You can reach her directly through her website, www.rolfingconnections.com.

References

Kirkness, Karen. 2021. Spiral bound. United Kingdom: Handspring Publishing Limited.

Bond, Mary. 2023. Body mandala: Posture, perception, and presence. Rochester, Vermont: Healing Arts Press.

Bond, Mary. 2018. Your body mandala: Posture as a path to presence. Maitland, Florida: MCP Books.

Bond, Mary. 2016. Heal your posture: A 7-week workshop. Available from https://vimeo.com/ondemand/healyourposture.

Bond, Mary. 2006. The new rules of posture: How to sit, stand, and move in the modern world. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Bond, Mary. 1969. Implications of the theory of structural integration for movement therapy. The Bulletin of Structural Integration 1(1):6-14.

Martin, Danièle-Claude. 2022. Living biotensegrity: Interplay of tension and compression in the body. Munich, Germany: Kiener.

Richardson, Carolyn. 1999. Therapeutic exercise for spinal segmental stabilization in low back pain. London, UK: Churchill Livingstone.

Rolf, I. P. 1978. Ida Rolf Talks about Rolfing and Physical Reality. (R. Feitis, ed.) Boulder, CO: The Rolf Institute.

Keywords

movement; balance; support; mandala; interstitium; fascia; tensegrity; biotensegrity; reflexive coordination; core stabilization; strength training; perception; presence; prevention; posture; structural integration; Dr. Ida Rolf; Hubert Godard; fascia hub; compression; tension. ■

View all articles: Articles home