ABSTRACT This article explores the necessity of liberating the planes of motion in the appendicular system through understanding the sequential spirals existing at all levels. Rolfing® Instructor Valerie Berg reflects on her brother’s experience with ALS (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis) and his loss of motor control in his appendicular structures. Berg herself has recovered from a serious accident to her own arm and hands. She applies this personal insight to teaching the true nature of the appendicular structures.

The first time I saw my brother faceplant was after he had lost the use of his arms to ALS (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease). It was horrifying. I cried. He was helped up and continued walking. This was not new to him. Over a period of twenty-five years, he slowly had lost the use of first, his right hand, then his right arm, then his left hand and arm, then, finally, both his legs, one at a time. The motor neurons die with ALS, not the sensory nerves, so he could still feel everything. He was not ‘paralyzed’ he just couldn’t move.

His appendicular system was defunct. Out of service. He was a trunk and a head and a voice in a wheelchair. His spinal and cervical muscles were what held him in balance in gravity and they eventually also became out of service. A neck brace held his head up and belts kept him upright. The appendicular system was limp rags. When he could still stand he would sometimes make movements where he would roll his trunk around and fling his arm up onto the counter where the two fingers that still worked could manipulate a toothbrush. His eyes and his voice became his way to manipulate and interact with his environment in all ways. He could bounce to musical rhythms. He would fly through space in his Bluetooth wheelchair directed by his head movements and a small screen. With no functioning appendicular system at all anymore, the wheelchair became his stability and allowed him to move. The last movements he could make with his legs were to lock his knees in a standing position and later, only a slight abduction/adduction of his thighs.

The stillness of his arms and legs was what struck people first. They would reach out to shake his hand, the way we reach into social interaction. Nothing responded except his shining eyes and warm voice explaining, “I can’t move my arms.” One index finger maintained its movement throughout the years. Nobody knows why. So, he could manipulate a few things with that one finger. His head movement from side to side directed his wheelchair, his eye movements and voice manipulated his mouse and computer functions. Amazon’s “Alexa” turned on his TV and called me on the phone. Apple’s “Siri”, of course, was indispensable.

His ability to remain upright in the seated position was tenuous without the use of his arms. We take this for granted. Spinal and core musculature balance us in gravity, but make one quick turn and notice how important your shoulder girdle and arms become to balance for this very subtle weight change. The appendicular system keeps us vertical.

In my last article, “The Complexity and Reasoning of Keeping 3D Hands and Fingers” (Berg 2020), I emphasized and showed the essential knowledge and use of the spirals/diagonals in the finger joints and hands. I also had temporarily lost the use of my arms and hands due to an unfortunate accident, where my car rolled over my left humerus and right hand. My balance was very fragile without the use of my arms. The dependence of my verticality on my arms was painfully evident. Hiking up hills without the ability to move my arms freely made me very unstable.

The Feet and Hands are the Antennae of our Appendicular System

Think about reaching for something. Eyes locate the object and most likely one sees texture, size, and distance as the hands prepare for grasping and holding. The shoulder girdle’s main purpose is to send our hands into space to interact with the environment. Most of us create enormous tension in the upper body to hold onto something or even to reach. We begin the movement with the shoulder musculature instead of the finger antennae.

The same three dimensionalities I found necessary in the hands are necessary for the feet. The feet and hands are the antennae of our appendicular system. Think about standing up and notice your feet searching for and finding their stability (or not!). The terrain is perceived by the foot and it organizes itself and its fascial complex to be able to support the body segments up to the pelvic girdle and onto the spine.

His ability to remain upright in the seated position was tenuous without the use of his arms. We take this for granted. Spinal and core musculature balance us in gravity, but make one quick turn and notice how important your shoulder girdle and arms become . . .

Gracovetsky’s Spinal Engine: Contralateral Movement in the Appendicular (1987)

Many are familiar with Serge Gracovetsky’s, PhD, videos that show a limbless person walking across the room on his ischial tuberosities.1 His point was to demonstrate that spinal rotational movement is the engine that moves us, not the legs. The legs fuel the spinal engine.

The pelvis, even without the femoral joints, would still need to be balanced. Dr. Rolf’s phrase ‘horizontalize the pelvis’ was all about the necessity for balance in the ilia so movement and force are transmitted to the spine via the ischial tuberosities in a balanced and mobile manner. With legs, the movement of the femoral head in the joint requires its full range of motion so as not to drag on the ilia via the myofascial components. The legs are either the fuel or the brake for the spinal engine (Gracovetsky 1987). If the freedom of the femoral joints and ilia movement exists so as not to pull or restrain its movement, then the spine can move in its spiraling fashion, which in turn gives our arms and shoulder girdle the range and mobility they must have to move into the world.

The shoulder and pelvic girdles, legs, feet, arms, and hands give us the stability and mobility in spiraling mode. It is the focus of this article to emphasize the spiraling sequences of the appendicular system that liberate and fuel our spine. Spiral sequences of the appendicular system allow for joyful movement and the ability to balance our heads in space, to allow us to orient, and to see where we are going.

The first creatures to stand on two legs were dinosaurs. They stabilized with a very long tail, huge toes, and flexed knees. Large, powerful legs were necessary without skeletal support under their pelvises. We were made to move. Our structure is such that our femoral joints from the pelvis to the feet are in line with gravity, perpendicular to the ground. But it is not a rigid line. There are myofascial sequences and transmissions of fascial connections all representing the three planes of motion. Our legs developed as limb buds growing out of the sides of the embryo and then they rotated around to the front creating fascial spirals.

Gracovetsky discusses the three planes of motion in the vertebrae and the movements they allow for: sidebending in the coronal plane, flexing and extending in the sagittal plane, and rotation in the transverse plane. Sidebending and rotation are the main drivers of the spinal engine. His theory of transmission of energy from the legs has three distinct pathways - superficial, middle, and deep – based on the spiraling movement of the foot and toe hinge that begins the whole process. Appendicular components have to have the three planes of movement to feed the spinal movement or we se the imbalanced structures that walk through our office doors. When the feet, lower legs, or thighs become bound and unable to complete their spiral potential, there is inhibition or restriction in the spinal movement. The ilia will show these restrictions that can begin either below or within the pelvic girdle soft tissue system. The ‘trouble’ can be ascending or descending. Restrictions could start with the feet and move up or start with the femur or lower leg and travel both up and down the body from there.

Chains of Movement

‘Chains of movement’ is not a new concept. Physiotherapist and anatomy/physiology instructor Françoise Mézières (1909-1991) worked on the subject in the 1940s. Gracovetsky has his transmission chains (1987) and physical therapist Luigi Stecco has myofascial chains or sequences (2004). All these concepts are valid because no movement is performed by one muscle connected to two bones, but rather by interdependent chain links that travel through the whole fascial body. “All are based on different theories but agree on the spatial organization of these connections. Dissection shows that these connections are found in the myofascial expansions and create an anatomical continuity between different muscles involved in the same directional movement” (Stecco, C. 2015, 242). The importance of the spiraling nature of every muscle fiber and their fascial wrappings is the key to seeing and working with freeing the appendicular system to its full function. A dynamic balance is necessary along the ‘chain’. Dysfunction shows up at a distance from a spiral gone rigid!

The linking joints and segments of the lower body can begin with the ‘juicy paw’ . . . Losing the fine and resilient movement in the foot and ankle sets us up for the look and feel of an aging person. A locked foot or ankle stops the spinal movement from occurring with ease.

Lower Body Appendicular

The linking joints and segments of the lower body can begin with the ‘juicy paw’. In my article, “Structural Aging - Part 1” (Berg 2014), I mention the twenty-six bones in each foot that need to rock and roll. Here are the sensitive antennae of the toes that do not function properly in many people. We need small movements in the tarsals and metatarsals that play the earth like the hands can play the violin. Pronation and supination need a navicular and a cuboid that can move. Thus, in landing on the lateral arch, the foot can pronate across to ‘toe-off’, feeding the knee and hip to find full extension. The biceps femoris then acts on the sacrotuberous ligament which translates to the opposite side of the lumbodorsal fascia feeding the contralateral motion of the two girdles. The functional foot sends the hip joint back into extension and keeps us from staying in a flexed hip, no-gluteal-use posture. Losing the fine and resilient movement in the foot and ankle sets us up for the look and feel of an aging person. A locked foot or ankle stops the spinal movement from occurring with ease.

In another fascial layer, the iliotibial (IT) band is stretched by a spiraling femur internally rotating, going to the gluteal muscles and latissimus dorsi to fuel the contralateral motion of the limbs. Spirals feeding spirals. The pelvic girdle is the transitional juncture for these potentially beautiful movements. It is the dynamic link between the spine and the lower legs. The spirals of the lower appendicular structures fuel the spirals of the spine if they are free to make their natural movements.

Pelvic Girdle as Transition

“The two girdles, pectoral [sic] and pelvic, determine the motor competence of the body. They implement the desire of the individual for movement and offer him [sic] the opportunity to exert a physical effect on his material environment. To some extent they are structurally homologous. However, the differences in primary function-motility in the arms versus weight support in the legs have blurred their similarity” (Rolf 1989, 212).

The pelvic girdle is a dynamic link between the spine and the lower legs. It is composed of three bones: the ilium, pubis, and ischium. It is like the switch on railroad tracks. Assuming there is balance at the pelvic level, movement and transmission of weight down into the feet – as well as moving up from the ground – will cross over at the pelvis into the trunk and upper girdle. There is potential for balance in all planes.

Sequences from Below

The foot is a sagittal plane pivot. The feet have a lateral and medial arch both sensing the ground. The medial and lateral components of the thighs mediate in the coronal plane. Each metatarsal has rotational, sagittal, and coronal plane ability, and each phalanx has the same. We all know how a bunion or hammer toe locked in its joint ‘decision’ changes the entire walk. The sequence of connections moving up is inhibited. It is useful to know the pathway that has been restricted by this one block. Then one can begin to see the compensations made based on the restricted plane of motion.

Forward movement in the sagittal plane and internal rotation ends in the hallux. If a bunion has now stopped the sagittal and rotational movement in the hallux, the rest of the foot must compensate, up and into the ankle and lower leg. “Before aberrations in the upper body can disappear, ankles must be reconstructed. Their lines of transmission freed, and structures made sturdy for their job of transmitting weight” (Rolf 1990, 45). Once the heel and forefoot are in contact with the ground, the ankle is the next site of movement. The ankle joint needs to dorsiflex and must expand to the widening surface of the talar dome. This is all dependent on the motion of the fibula rotating up and in and the reverse motions with plantar flexion. If the foot does not pivot sagittally it will negate the responsive hip motion for extension. Gracovetsky even goes so far as to state, that failure of the sagittal plane pivotal action of the foot results in a cyclic breakdown in maintaining an erect posture and actually causes flexion deformity via a compensatory process (1997).

Transmission of weight requires all planes of motion to be spiraling down into the foot, back up to the pelvis and spine, and then generate the freedom of movement for the shoulder girdle. The sagittal plane task requires the control of the hip, knee, and ankle angles during standing. We all learned ‘toes up, knees up’ in Rolf’s yoga. This is cementing the sagittal plane between the joints.

Abduction and adduction fascial sequences end in the middle toes with external rotation and the return movement ends in the little toe. Again, the toes are the antennae organizing all this sequencing above. The horizontal plane has to balance the sagittal for the vertical in order to not collapse. What we see in the aging structure is the shuffling gait characterized by a narrow focus in the ‘sagittal only’ plane of movement. Support and movement education in the coronal plane is essential for balance. Weakness in abduction/adduction leads to falls with any perturbation from the side.

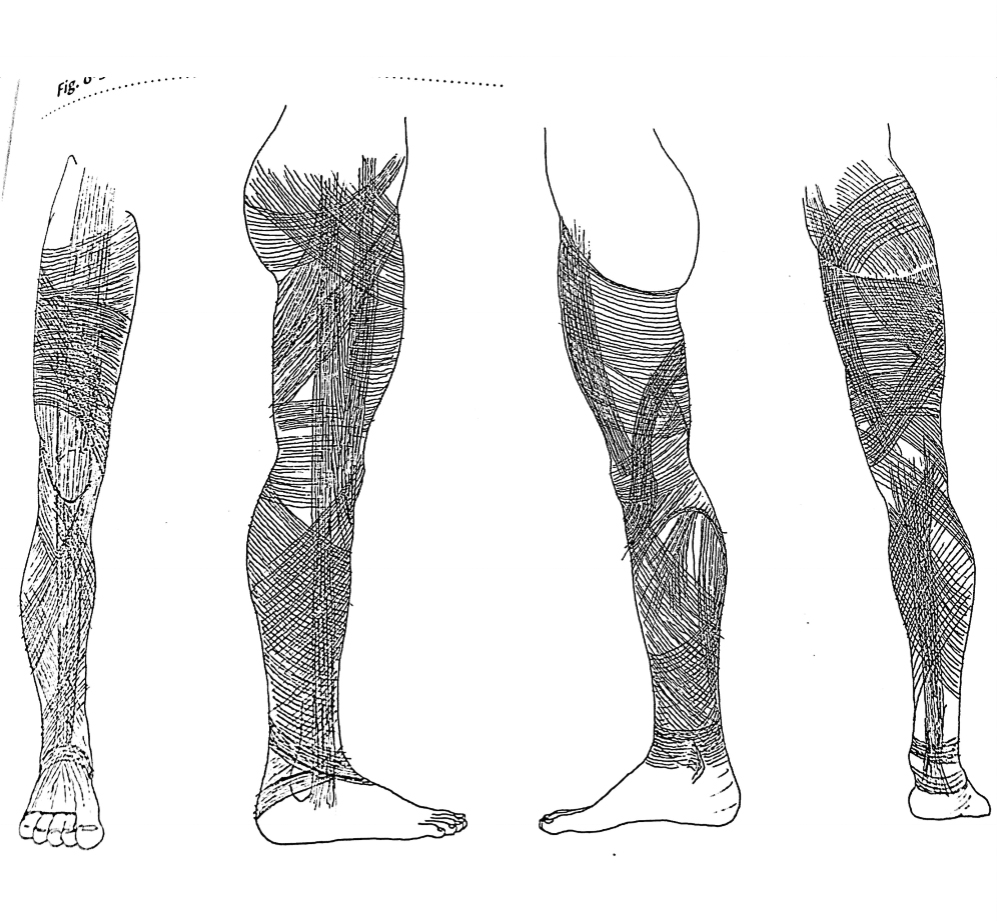

The lower limb fascia, as seen in see Figure 1, is composed of vertical, oblique, and horizontal fibers that are woven and interlaced together. “The system is continuous with the fascia of the trunk through the gluteal aponeurosis” (Paoletti 1998, 53). The legs were made to function and move us in all directions. “If stress is to be relieved, it is important that no myofascial component contribution to pelvic balance be overlooked” (Rolf 1989, 125). Understanding the fascial sequencing of the three planes is more useful than just working with muscle/fascia restrictions.

Gracovetsky’s ‘transmission paths’ as stated earlier start with landing on the foot, spiraling the foot to a toe-off that sends the knee into screw home2 and the thigh into extension with the lateral hamstring activating the sacrotuberous ligament. The screw home requires the rotation of the tibia and fibula, and then an unwinding of them as well. The femur is also adducting and abducting, rotating in and out through the entire gait movement. Then the movement comes into the pelvic girdle in the hopes that the ilia will anteriorly and posteriorly tilt in response to the spiraling movement coming from the foot to the rotating femur. Gracovetsky adds a third, deeper transmission sequence that triggers the multifidi and transverse abdominis to support the spine in this movement (1987).

Loss of internal or external rotation in any of the lower limb bones due to myofascial restrictions is going to change the range of motion of each joint, as well as change the spinal movement and restrict the ability to move in all planes of motion for the entire body. Weak hip adductors destabilize the hip in the coronal plane in a unilateral stance. Seeing legs free of each other and not hooking the pelvis means tracking where the spirals have lost their transmission to the next sequence. A rotating pelvis is what can bring the acetabulum forward in the gait. The pelvic girdle needs to rotate as a unit on the femoral heads in the transverse plane toward the weight-bearing limb.

Thus, the ligamentous bed of the femoral head is crucial for the three planes of movement of the leg. In external rotation the pubofemoral ligament is taut and the ischiofemoral is slack and in internal rotation, it is the opposite. In abduction and adduction, we are dealing with the ischiofemoral, iliofemoral, and iliotrochanteric ligaments – all needing to be either taut or slack. All these ligaments prevent excessive movement, but respond to the three planes of movement necessary in walking.

Where miga restricted femoral joint?

- Adductors at the ramus and the knee (‘Fourth Hour’) so the leg can reach without closing at the pelvic floor;

- Gluteal muscles and IT bands so that the leg extension and toe hinge can trigger the pull to the limb into contralateral movement;

- The six deep lateral rotators, including the piriformis, that hold tight onto the femur;

- Pectineus and iliacus (‘Fifth Hour’) for restriction in the front sagittal plane;

- Sacrotuberous ligament and obturators in the back of the pelvic floor to liberate the pelvis from the leg spirals.

It is necessary here to mention the vestibular system of the inner ear. The three pairs of semicircular canals, literally, are an example of the x-, y-, and z-axes – all three planes of motion. If there is vestibular inhibition or an inner-ear problem, the hip and ankle joints will flex and brace. With focal vision, vestibular function is inhibited and changes the gait stride length. Thus, even our eyes need the full range of motion to keep the gait free. The vestibular system links directly to the brain where motion happens on spatial planes, not on individual muscles. Our entire functioning from our feet to our inner ears is in three planes of motion in relation to gravity and is always working to stay vertical. It’s not surprising that our appendicular system needs a sense of the horizontal plane as well as the coronal plane for balance, i.e., the need for quick stability in side-to-side motion in the hip joints, the quick response of our arms to reach out to steady ourselves, our inner ears signaling to our brain where we are, the femoral joint stabilizing in the coronal plane all the way down, to the ankles stabilizing in the sagittal plane, and, of course, all the spiraling movements of the twenty-six bones of the foot to sense the ground.

It is necessary here to mention the vestibular system of the inner ear . . . If there is vestibular inhibition or an inner-ear problem, the hip and ankle joints will flex and brace.

Appendicular: The Upper Body

As I mentioned, losing the use of my left arm and right hand for around six months from my car rolling over me, led to a deep study of my own movement and an understanding of what was needed to regain complete dexterity and range of motion. Watching my brother’s gradual loss of his arms was humbling, to say the least. First, he needed to be fed. Jokingly, we were told we were never fast enough, or we didn’t put enough in his mouth. He was a loving, spirited man who was never complaining or wallowing in self-pity. But one could see and sense the frustration he experienced for his lack of power to manipulate and order his universe and the difficulty of having to wait for an ‘outsider’ to take the place of his arms and hands. He said the hardest thing was not being able to touch anyone and fewer people touching him. Losing the use of his arms and hands seemed to be a bigger loss than his legs and his ability to walk. I used to place his hands on his dog or his kids so he could feel them. I would move his hands for him to stroke the dog or the bodies of people he loved. Touching, reaching, making things, ordering the environment, and making the world as we want it happens through our arms and hands.

Floating him in his pool was his ecstasy. I could move his shoulder girdle in a wider range of motion in water. Being out of gravity was a huge relief. It was the movement and the skin contact with water that was so important. Once out of his wheelchair, he could change his spatial orientation. The water allowed planes of movement to return to his body. I would roll him over with his face briefly in the water, floating on his belly.

It was interesting that his eyes became his hands. He could move the mouse on his computer screen with his eyes. “The geometry of eye movements within the orbits corresponds remarkably to that of the head of the humerus within the shoulder joint - the brain points the arm and finger as accurately as it points the eye” (Wilson 1999, 88). Also, the ocular muscles have a connection with the myofascial sequences. His eye movements were like shoulder movements if he could have moved. Later, when he would lose the ability to speak, his eyes again moved a computer cursor that would speak for him. Eyes, inner ears, and humeral joints all keep us vertical through spirals in the horizontal and all planes of movement. We can also track the spirals in the arms and shoulder girdle that are responding to the spiraling motions of the spine fueled by the planes of motion in the feet and legs if the gait has sent that ‘fuel’.

Missing Planes

Luigi Stecco (2004) uses his concept of myofascial sequencing to describe how to work with restrictions. In all movements it is useful to ask our clients to watch for the ‘missing planes’. So often we ask the client to “raise your arms up and out to the side.” The variability of how people move their arms is huge. Emotions ride in our arms and hands. We reach, we push, we pull, and all these are influenced by our interactions, present and past, with the environment and with our relationships. Spreading our wings fully takes some attention. The restriction of the multiplanar movements in the arms, starting even with the fingers, can impede the trunk and spinal movement. Where does the arm start losing its ability to rotate as it comes up and out?

The forward and backward movement of the arms in the sagittal plane helps maintain our verticality. Internal and external rotation of the arms helps to maintain coordination in the horizontal plane. Think about our contralateral movement that is inherent. Our arms swing forward but they also (given freedom) can inwardly and outwardly rotate. They abduct and adduct to balance our legs, moving in different directions, throwing our equilibrium into a balancing act. Each ulna and radius also rotate opposite each other. The ulna has important evolutionary freedom that changed from direct attachment to the carpals to a detachment that gave us brachiation and more range of motion. It used to be attached to the carpals. The rotation of our thumb in relation to our elbow is because the radius rotates at the elbow joint. Our forearms have pronation and supination. Each finger has its own myofascial sequence connection up to the shoulder girdle and to the cervical spine. Even the fascial fibers have multiplanar arrangements. The spirals of the upper appendicular complete the spiraling spine and fuel the upper thorax motion, while stabilizing our head and eyes.

The Shoulder Girdle

The shoulder girdle is composed of the clavicle, scapula, and humerus. The scapula has upward rotation (from the upper and lower trapezius), lateral movement (from the serratus anterior), movement down and out (from the lower trapezius), and finally, elevation (from the upper trapezius). The scapula steers the clavicle into its sternal socket. Any restriction of these movements will change the movement of the clavicle and humerus. In the Gracovetsky chain, the shoulder girdle and arm swing are fueled from the opposite leg and hip through the latissimus dorsi pulling the rib cage and shoulder back (1987).

The clavicle can rotate slightly at the sternoclavicular joint and it can elevate and depress. This is the only direct bony attachment the shoulder girdle has to the axial skeleton. The humerus has the most range of motion due to its need to be ‘in the world’ in order to manipulate, grasp, and order. Abduction and adduction, internal and external rotation, flexion and extension, and circumduction all happen at the glenohumeral joint. The need for differentiation becomes very clear at this joint. Our freedom in the arm swing is crucial for the stability and efficiency in our movement.

He said the hardest thing was not being able to touch anyone and fewer people touching him. Losing the use of his arms and hands seemed to be a bigger loss than his legs and his ability to walk . . . Touching, reaching, making things,

ordering the environment, and making the world as we want it happens through our arms and hands.

The Elbow

The elbow is where the shoulder and the hand meet. There is both hinge and rotational movement from the humerus meeting the ulna and radius. It has sagittal plane movement, stabilizes lateral and medial movements, and rotary movement at the head of the radius. Extrinsic myofascia of the hand comes from the forearm. The interosseous membrane anchors four of the muscles that move the thumb, which need to have multiplanar movement for manipulation. Many structures from the upper arm meet at the elbow.

The cubital fossa is a key area to address in any arm work. It is a place where forces meet and can become glued. The lateral and medial intermuscular septa can be accessed here allowing for rotation of the humerus. The distal bicipital tendon and proximal brachialis meet here and almost always need differentiation. The pronator teres fascia crosses the bicipital aponeurosis. The coracobrachialis and flexor carpi radialis meet here and all are contained in the antebrachial fascia forming a spiral.

The back of the elbow is where the triceps brachii aponeurosis meets the wrist and hand extensors at the lateral epicondyle. These are all myofascial sequences that do not stop and start, they are continuous with each other and need the freedom to meet the demands of rotation and hinging. The elbow is the mediator for how our shoulders send our hands into space. One of the earliest imperatives for maturing is our impulse to reach or grasp. The elbows held rigidly in can impede this basic impulse. The arm basically stops at the elbow and the rest is modification and adaptation to the spiraling needs. This is like the lower leg and its need to adapt.

The Wrist

The wrist cannot be left out as the movement here is crucial for everything we do with such small articulations. The ulna does not articulate directly with the carpals, so in pronation, it slides distally up two millimeters in relation to the radius. There is flexion, extension, radial deviation, and adduction. Go ahead and gesture like a conductor in front of the orchestra counting the beats, right now, with just your hand and fingers with an imaginary baton, and see the nonstop spiraling movements – hopefully! It is an interesting fact that we have five fingers, four distal carpals, four proximal carpals, two lower arm bones, and one upper arm bone, all supporting the next segment. A good body reading for the upper appendicular is to ask your client to crawl and watch the arches of the hands and the angle of the elbow. Where do they initiate movement from? Do they reach, do they push, and does the humerus rotate and extend? Explore the ranges of motion by bringing the arm up and putting the hand behind the head or the arm behind the back. Where is the loss of the spiral? The humerus? The elbow? The forearm? The wrist? The fingers?

Evolutionarily, the coronal plane was the first plane of movement to be mastered in the aquatic environment. Coming on land developed the sagittal plane and our humerus became important. Later, with complex motor activities, the horizontal plane developed. The humerus has influence over all these movements, which help keep us balanced in the vertical.

The humerus has the most range of motion due to its need to be ‘in the world’ in order to manipulate, grasp, and order. Abduction and adduction, internal and external rotation, flexion and extension, and circumduction all happen at the glenohumeral joint . . . Our freedom in the arm swing is crucial for the stability and efficiency in our movement.

Myofascial Sequencing of the Arm

The deltoid and pectoral fasciae are involved in almost all the myofascial sequencing of the arm. The three heads of the deltoid need to be differentiated to liberate the spirals. The balancing of the latissimus dorsi and pectoralis major attachments on the humerus in the 'Third Hour' is key to the internal and external rotations. The deltoid exerts traction on the intermuscular septum, while the brachioradialis and extensor radialis carpi are also inserted here. These need to be differentiated for lateral motion and abduction. The deltoid heads lie on top of the brachial fascia. The latissimus fascia spirals from the back to the front of the humerus and the teres major fascia moves into the brachial fascia, and all of this goes on under the deltoid heads.

For forward motion, the myofascial sequence goes from the clavicle to the pectoralis major to the bicep brachii, then to flexor carpi radialis, and to the thumb. When you see a restriction in this plane, track the fascial binding in this sequence. “In all vertebrates, the retro-motion (extension) sequence is always located on the ulnar side of the upper limb” (Stecco, L. 2004, 126). This sequence goes from the trapezius to the deltoid, to the triceps, to the extensor carpi ulnaris, to the little finger. One can imagine if you break your little finger how it might interfere with this plane of motion. According to Luigi Stecco (2004), adduction of the arm goes from the latissimus to the biceps to the triceps to the flexor carpi ulnaris to the lateral arch of the palm. This fascial sequence also comes into the axillary fascia, which is where we work in the Third Hour. An interesting side note here is that the pharyngeal fascia connects to the axillary fascia, thus another appendicular connection into the axial. With abduction, one wants to look at the connection of the trapezius to the deltoid, the extensor carpi radialis, and the interosseous membrane.

The internal rotation sequence is from the pectoralis major to the subclavius, to the subscapularis, to the pronator teres, to the flexor digitorum, and then to the lateral three fingers. External rotation goes from the supraspinatus to the supinator, to the extensor digitorum longus, and to the lumbricals of the fingers. These describe Luigi Stecco’s myofascial sequences (2004). All of these sequences are spirals in nature. The appendicular is our spatial perception that communicates with the brain and eyes. Even the architecture of the fascial fibers reveals the planar structures. Reaching out into space begins with the rotations, extensions, and flexions of the fingers into the different movements of the ulna and radius, flexing and rotating at the elbow. The humerus is fed by the movement of the scapula rotating and flexing towards the desired object and hopefully coordinating with the exquisite movements of the eye and, of course, managed by the inner ear.

Structural aging, which I define as loss of planar movement in the body, can be helped by our work. Structural aging looks like a structure that lives in a small, limited space. The eyes mostly look sagittally and down. The shoulder girdle lives in the sagittal plane and a restricted range of motion here drags the rib cage forward and down along with the head. The feet, not moving as juicy paws, hold tight at the ankles, which are not moving in their full, delicious flexion and extension – thus, no spirals in the tarsals, but now a painful shuffle, which prevents the joyful hip extension in the full gait. We break down into living in the sagittal plane, bent over and looking down. Loss of the lumbar curve, flattening of the cervical curve, losing shoulder girdle range of motion, and more hip pain and knee pain, all lead to balancing that is challenged. The appendicular fuel no longer feeds the vitality of the spiraling movement of the spine. Contralateral movement is halted. Reduced arm swing creates compensatory hip imbalance and low back pain. Our expression is blocked or limited.

We can see the person under the wing of the shoulder girdle. How does it fit? How does the shoulder girdle move over and around us? Where is the freedom of the base of support - the pelvic girdle - to translate the gait as the dynamic link between the spine and the lower legs? Does the person have a stable base from which the upper girdle can function? The years in age do not matter. A teenager can have this structural aging.

Our winding, vertical, diagonal, and oblique fibers that intertwine and weave together throughout the appendicular system and into the axial spirals help to keep us expressing complexity and variability. Watching the recent olympian win the gold medal in ice skating showed the nonstop spiraling of his appendicular system. Marcel Marceau (1923-2007), a famous mime, pantomimed the act of sewing. People sitting very far away could tell what he was doing because of the way he moved his arms, letting his sternum direct the movements. All the planes of the movement were exaggerated – each finger movement to the forearm, then to the humerus, and finally to the chest. These qualities are the hallmark of healthy human functioning. We were made, down to the very fiber, to interact with the world, and each other, in multiple planes with our spiraling appendages.

Endnotes

Screw home mechanism of the knee joint is when the tibia externally rotates slightly and the femur internally rotates slightly during extension (Physiopedia 2022).

Valerie Berg has been a Certified Rolfer® since 1988, a Certified Advanced Rolfer since 2000, and a member of the Dr. Ida Rolf Institute® faculty since 2003. She is also a Rolf Movement® practitioner and has been influenced by her history as a modern dancer, by Hubert Godard, and by yoga. She worked in Guatemala for five years doing Rolfing sessions during that country’s civil war and, thus, pursued Peter Levine’s Somatic Experiencing® trauma training afterward. She has been practicing in New Mexico for thirty-two years and alternates that with working in San Diego, California. Tango, kayaking, sculling, and yoga keeps her moving and interested in the vitality of our bodies continuing through the years. The joy of movement for the human body is what brought her to become a Rolfer and now continues to be what she teaches to anyone of any age through Rolfing SI.

References

Berg, V. 2014. "Structural aging part 1 – Finding grace in gravity.” Structural Integration: The Journal of the Rolf Institute® 42(2):40-8.

———. 2020. “Complexity and reasoning of keeping 3D hands and fingers.” Structure, Function, Integration. Journal of the Dr. Ida Rolf Institute 48(1): 20-28.

Gracovetsky S. 1987. The spinal engine. New York, NY: Springer Vienna Publishers.

———. 1997. “Linking the spinal engine with the legs: A theory of human gait.” In Movement, Stability and Low Back Pain: The Essential Roll of the Pelvis, Chapter 20. Editors A. Vleeming, V. Mooney, T. Dorman, C. Snijders, R. Stoeckert. London, UK: Churchill Livingstone.

Paoletti, S. 1998. The fasciae anatomy, dysfunction and treatment. Seattle, WA: Eastland Press.

Physiopedia. 2022. Screw home mechanism of the knee joint. Accessed May 12, 2022. Available from https://www.physio-pedia.com/Screw_Home_Mechanism_of_The_Knee_Joint.

Rolf, I.P. 1989. Rolfing – reestablishing the natural alignment and structural integration of the human body for vitality and well-being. Rochester, VT: Healing Arts Press.

———. 1990. Rolfing and physical reality. Rochester, VT: Inner Traditions International, Ltd.

Stecco, C. 2015. Functional atlas of human fascial system. London, UK: Churchill Livingstone.

Stecco, L. 2004. Fascial manipulation for musculoskeletal pain. Padua, Italy: Piccin Nuova Libraria S.P.A.

Wilson, F. 1999. The hand. Toronto, Canada: Penguin Random House Canada. ■

View all articles: Articles home